By Brian McCandless

In the early twentieth century, in the UK and the USA, ‘music hall’ and ‘vaudeville’ compositions were the most popular form of song. They were listened-to and sung along with in ever-expanding theaters in which musical acts were gradually overshadowing other variety acts (animal imitators, acrobats, human freaks, conjurors, magicians, etc.). The industry became dominated by chains of theatres like Moss (UK), Stoll and Thornton (UK), United Booking Office (USA) and Beck’s Orpheum Circuit (USA), and by music publishers selling large volumes of sheet music. Music hall seats were affordable and attracted a largely working class audience, for whom a gramophone would generally have been too expensive. Although many ordinary people had heard gramophones in seaside resorts or in park concerts organized by local councils, many more would discover the gramophone while in the army, since gramophone manufacturers produced large numbers of portable gramophones “for our soldiers in France.”

Although the song repertoire was dominated by comic pieces, sentimental love songs and dreams of an ideal land (Ireland or Dixie in particular) made up another significant category. Practically all the songs of the era are unknown today; several thousand music hall songs were published in the UK alone during the war years. The singers moved from town to town, many just scraping together a living, but a few making a lot of money. The key stars at the time included Marie Lloyd, Vesta Tilley, George Formby, Sr., Harry Lauder, Gertie Gitana, Harry McDonough, Harry Champion, and Enrico Caruso.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, many songs were produced which called for young men to “join up,” influenced by the British victory in the 1899-1902 South African campaign called the Boer War. Examples of recruiting songs include “Good-Bye Dolly Gray”, “We Don’t Want to Lose You, but We Think You Ought to Go”, “Now You’ve Got the Khaki On” (a reference to the adoption of khaki uniforms by the British army in the late 1890’s) and “Kitcheners’ Boys” (referring to Field Marshall Horatio Kitchener who led the Boer defeat). Scottish regiments heard and sang songs such as “Lochanside”, composed by Pipe Major John MacClellan of Dunoon during the Boer War Battle of Magersfontein.

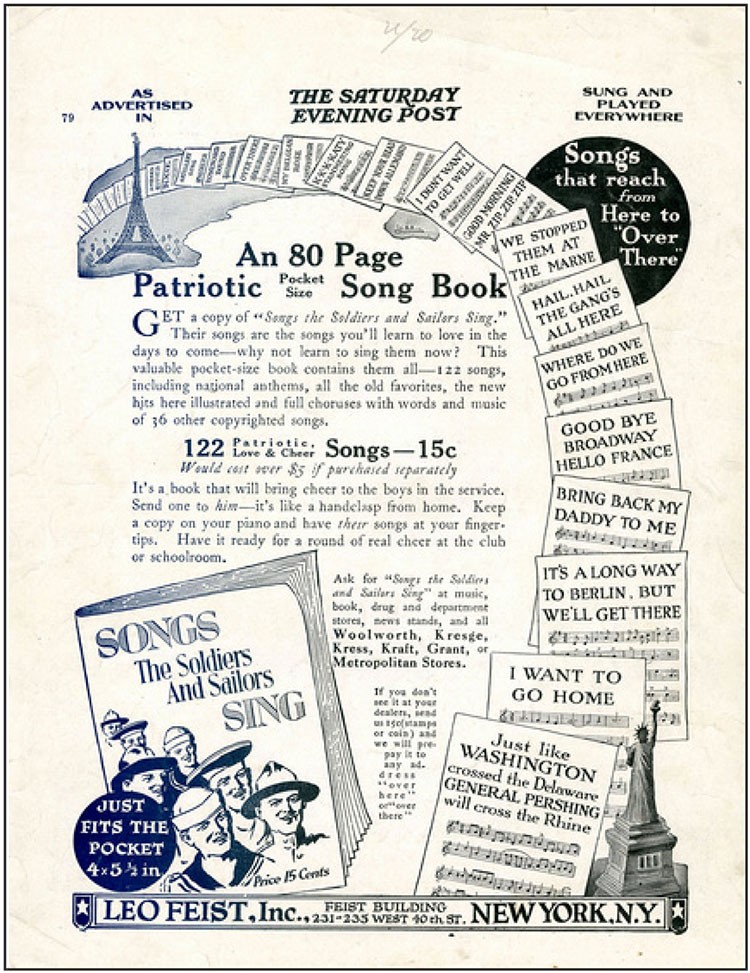

After a few months of war and rising numbers of deaths, UK recruiting songs all but disappeared, and the 1915 “Greatest Hits” collection published by Francis and Day contains no recruitment songs at all. The music hall songs which mentioned the war, roughly a third of the total produced, were more and more dreams about the end of the war—“Keep the Home Fires Burning” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary” are two well-known examples. At the entry of the USA into the war in 1917, George Cohan’s song “Over There” sold over 2 million copies and earned him the US Congressional Gold Medal. Because there were no radios or televisions that reported the conditions of the battlefields, Americans had a romantic view of war.

It was almost impossible to sing anti-war songs on the music-hall stage. The managers of music halls would be worried about losing their license, and the singalong nature of music hall songs meant that one needed to sing songs which had the support of the vast majority of the audience. In the music hall, dissent about the war drive was therefore limited to sarcastic songs such as “Oh It’s a Lovely War” or bitter complaints about the stupidity of conscription tribunals (for example “The Military Representative”). When the anti-war movement had gained a mass audience, for a few months in 1916, anti-war music hall songs from the United States such as “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” were sung at anti-war rallies and meetings, but not on the music hall stage. The old English song “Amazing Grace,” composed by John Newton in 1779, was undergoing a revival due to the efforts of a publisher named Edwin Othello Excell who published it in a series of hymnals arranged for use in urban churches and larger church choirs. Several editions featuring Newton’s first three stanzas and the verse previously included by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin were published by Excell between 1900 and 1910, and his version of “Amazing Grace” became the standard form of the song in American churches and would have been popular during the First World War.